What does it mean to be gay? Or even heterosexual? Is it defined by the body that one is born with? Or the presentation and modification of one's natal body? These questions surfaced while observing a Twitter controversy where an OnlyFans creator was attacked for performing with an FTM partner. At the heart of the pile-on was an anxious debate: what constitutes gayness? Can sex between a cis man and an FTM individual still be labeled homosexual?

This is not merely an abstract philosophical query. These questions gain real traction in a cultural moment obsessed with identity classification and moral performance. What about cis men who identify as homosexual but sleep with women? Or heterosexual men who sleep with men or trans women? Does the consistency of desire lend one more legitimacy to their identity than another? Is a "congenital homosexual"—someone who feels they have always been gay—more worthy of respect or rights than someone who chooses homosexuality as a mode of living, resisting heterosexual scripts?

The intensifying visibility of queer and trans people in the mainstream has surfaced contradictions that were once buried beneath political solidarity. During the campaign for marriage equality, these questions were set aside in favor of the universalizing rhetoric of "love is love." But in the wake of that political victory, the cracks have begun to show. Why is male bisexuality often treated with contempt by both straight women and gay men? Does this reflect a larger discomfort with sexual ambiguity?

These questions are not new. In the late 19th century, scandals like Oscar Wilde's trial or the Eulenburg affair brought homosexuality into public consciousness. These events changed not only how homosexual desire was perceived, but also how all male intimacy was scrutinized. The emergence of psychology and sexology attempted to offer answers by pathologizing or classifying homosexual desire. Yet the same questions linger today, unresolved, because the discourse has always been as much about social order as it is about individual experience.

As queer culture becomes mainstream and as trans identities reshape public conceptions of gender, the fragile alliance that once constituted the LGBTQ+ community begins to show strain. How can a community composed of groups with radically different ideological and ontological commitments cohere? What bonds exist between someone who believes gender and sexual difference are biologically innate and someone who insists these are social constructs?

Perhaps we need to recognize that the original bonds of this coalition were not metaphysical but political—a shared experience of marginalization, a shared enemy. But without that pressure, we are left with the question: what is this thing called "queer identity"? Is it a lived reality? A cultural aesthetic? A refusal? A performance?

To explore this, one must navigate the terrain of desire itself—its contingency, volatility, and symbolic weight. In Eroticism, Georges Bataille suggests that the sacred and the erotic both arise from the same rupture—the breaking of taboos. In The Pure and the Impure, Colette refuses to reduce sexuality to essence, instead seeing it as a zone of mystery and negotiation. And in What is Sex?, Alenka Zupančič reminds us that sex is not simply an act but a cut in the symbolic fabric—a place where meaning disintegrates, only to be reborn in forms we cannot always predict.

What if we accepted that homosexuality, as with all desires, is disordered, but not in the moralistic sense that seeks to erase or correct it? What if it is disordered in the way that all truth-telling is disordered: disruptive, defiant, and generative? For some, transgression leads to ruin. For others, it is the condition of lucidity. Some are destroyed by entering liminal zones of desire; others are refined by them.

Religion may offer a moral vision in which sublimation and surrender are ways of orienting desire toward a transcendent good. Yet for others—especially those seeking lucidity or existential realism—desire is not to be surrendered to or sanctified but mastered, deconstructed, and negotiated. Holiness, then, is not moral perfection but the relentless clarity of asking, "What is this love for?" and choosing the form it will take.

In the end, queer identity may not be a stable category at all. It may instead be a question posed endlessly in response to power, tradition, and the body itself. And that question cannot be answered universally. It can only be asked—seriously, vulnerably, and without shame.

Yet if queer identity is not a fixed position but a site of continual questioning, then the ethical orientation we bring to that questioning becomes paramount. Without the organizing threat of external condemnation, what disciplines desire internally? What calibrates its honesty?

One possibility comes from an unlikely source: the stony theology of John Calvin. Queer therorist would dismissed this approach as a repressive force, Calvin’s framework offers not a rejection of desire, but a confrontation with its unruly truths. His emphasis on the coram Deo life—the life lived openly before the face of God—demands a clarity that is not moralistic but diagnostic. Here, we are not asked to purify ourselves through identity, but to submit identity itself to judgment.

What emerges is a paradoxical ethic: one that does not idealize sexual liberation nor enshrine repression, but treats desire as a site of sacred and dangerous knowledge. This is what I call Calvinist lucidity—a mode of existential and erotic honesty that sharpens the very questions queer thought has long been asking.

Defining Calvinist Lucidity

At the heart of this Protestant erotic ethic lies a mode of spiritual clarity that borrows from John Calvin’s severe diagnosis of human desire. Calvinist lucidity can be characterized by several key features:

Coram Deo Consciousness: The individual stands continually “before the face of God,” acknowledging that no action or impulse escapes divine scrutiny. David wrote in Psalm 139:1-4 that God observes his habits even to his deepest thoughts. This creates a posture of radical honesty, in which one refuses to hide desire behind socially approved masks. This is illustrated in Hebrews 4:12-13, where the Bible is depicted as a double-edged sword discerning one's thoughts and the heart's intent.

As Calvin observes in his Commentary on the Psalms, Psalm 139 is not meant to flatter but to ‘terrify the conscience’ into truthfulness. Likewise, in Institutes 2.7.7, Calvin describes the Law of God as a mirror that reveals external actions and internal corruption. Just as a mirror reveals spots on the face, so too the Law reveals “the uncleanness of our nature.” Scrutiny is not merely an act of guilt but of grace, for in Calvin’s view, self-examination is the “principal exercise of repentance” (Institutes 3.3.19). To live coram Deo is to submit even desire to the blade of truth, not to shame, but to clarity.Diagnosis of Concupiscence: Inspired by Calvin’s Institutes 2.1.8–9, concupiscence (“the fountain of sin”) describes desire as a perennial source of disorder that must be neither naïvely embraced nor simply repressed, but confronted with sober self-awareness. Scripture teaches that “desire when it has conceived gives birth to sin” (James 1:15) and that the Law exists “to make us know sin” (Romans 3:20). In this view, sin is not only transgression against divine commands, but a disordering of love.

In James K. A. Smith’s "Desiring the Kingdom", he builds on Augustine’s precept “You are what you love” to argue that our affections shape our identity, so desires must be oriented rather than simply indulged or silenced. This resonates with Zupančič and Žižek’s insight that desire is a rupture in the symbolic order, a “crack” that demands interrogation rather than naive obedience or denial.

Suspicion of Theatrics: Calvin was wary of religious and moral theater—rituals or dogmas that paper over the human heart’s duplicity. Jeremiah 17:9 states that the heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked: who can know it? Calvinist lucidity resists both sentimental piety and performative virtue, opting instead for a stripped-down, unvarnished self-appraisal.

How many people know of individuals who repented of their sins in Big Tent Revivals only to go back to them a couple of months down the road? Such scenes dramatize the very condition Calvin warned against, emotional fervor that conceals an unchanged heart. A psychodramatic act that mistakes emotional intensity for moral transformation.

Self-Mastery, Not Self-Worship: While acknowledging the power of desire, Calvinist lucidity insists on human responsibility to choose its course. This is not a triumph of will but a humble exercise of freedom: mastering impulses without claiming domination over God’s sovereignty.

Grace as Unmerited Clarity: In a Calvinist register, grace does not obliterate concupiscence but illumines it. Grace is that sober gift of insight—an unexpected persuasion toward truth that does not override human agency but sharpens it.

By integrating these elements, Calvinist lucidity offers a distinctive stance toward erotic life—one that fully acknowledges disorder, refuses both hedonistic abandon and moralistic repression, and orients desire through the sharpened lens of conscience.

Calvinist Lucidity and Contemporary Queer Theater

While Calvinist lucidity draws on sixteenth‑century Reformation theology, its principles resonate strikingly with, and offer pointed critiques of, today’s queer discourses on identity performance, therapeutic culture, and online virtue economies.

Identity Performance

Judith Butler’s concept of gender performativity argues that gender (and by extension sexual identity) is constituted through iterative acts—stylized repetitions that produce the illusion of a stable self (en.wikipedia.org). In Gender Trouble, Butler writes that “gender is performative… a set of repeated acts within a highly rigid regulatory frame” (en.wikipedia.org). Calvinist lucidity challenges this theatricality by insisting that true identity cannot be sustained by performance alone, but must stand coram Deo, under the diagnostic scrutiny of divine truth.

Identity, while not merely performative, represents an ever-shifting negotiation between inherent biological factors and social norms. Although social constructs regulate identity, individuals possess the agency to engage with and influence these norms, acknowledging that society itself is not static. However, individuals cannot unilaterally determine their roles; even in cultures recognizing third genders, such roles are often established to serve societal structures rather than individual preferences.

Therapeutic Culture

Contemporary therapy often integrates queer theory, viewing identity through narrative and discursive lenses. Julie Tilsen, in Therapeutic Conversations with Queer Youth, highlights how therapeutic dialogues can assist queer youth in transcending homonormativity by constructing "preferred identities". However, Calvinist lucidity cautions that such re-narrativization might serve as a substitute for genuine self-examination, potentially transforming pride into another mask rather than unveiling the heart's duplicity.

This therapeutic re-narrativization is in contrast to the pre-Stonewall cultural expressions of Auden, Spencer, and Isherwood. In their writings, queerness was often portrayed as an intrinsic aspect of human experience rather than a focal point of struggle. The work of Auden and Stephen wrote queerness as a thread in the tapestry of human experience. Isherwood's A Single Man delves into themes of homosexuality and sexuality more as elements of the human condition than as declarations of queer identity.

Online Virtue Economies

On social media, virtue signaling has become a lucrative currency. The CEPR finds that tweeting #BlackLivesMatter or similar hashtags can confer social capital, even if it involves minimal personal commitment. Researchers at Sussex warn that digital activism often slides into “slacktivism,” where clicks and shares substitute for sustained engagement.

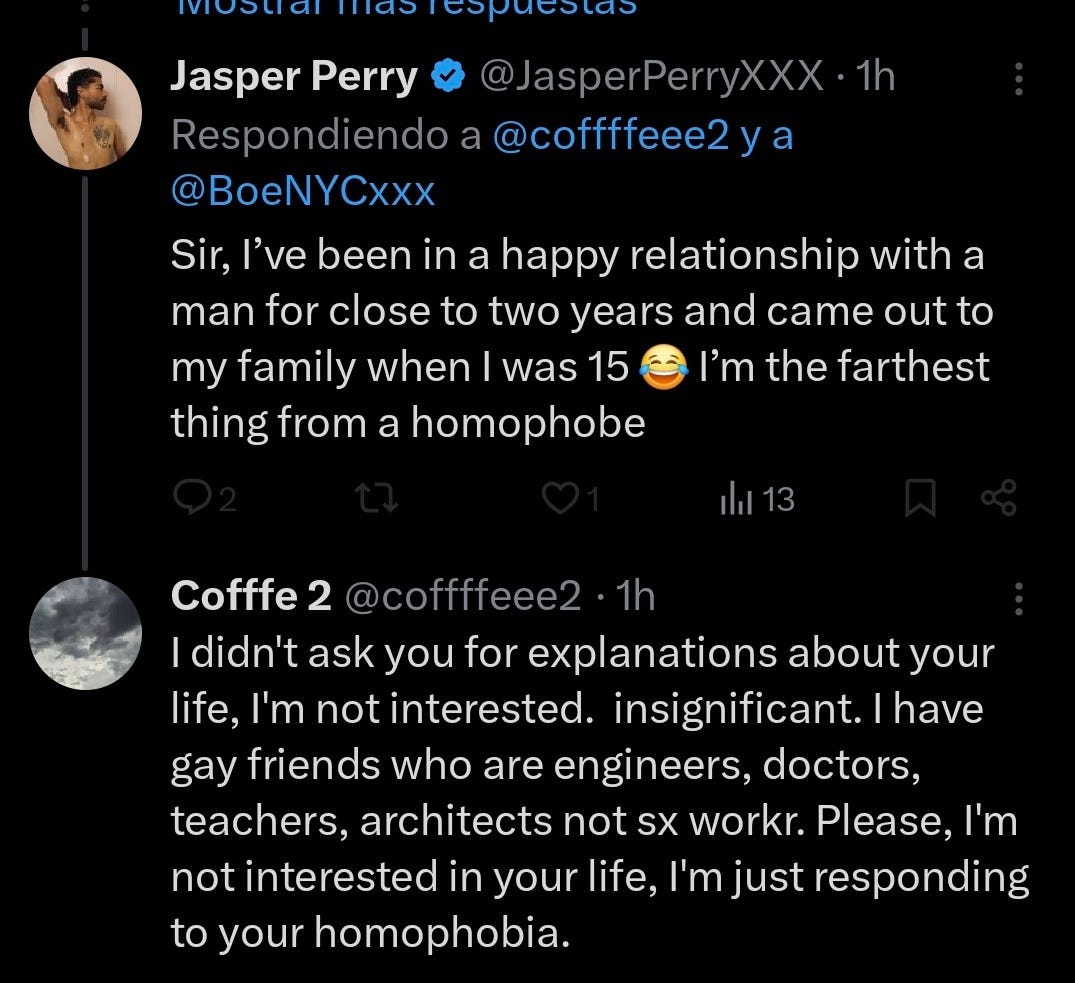

This parallels the recent trend of porn watchers calling out self-identifed gay creators for “performing“ with ftm men and biological women. There are extensive online discussions on LPSG (NSFW) where porn "fans" complain and harrass onlyfans creators for their performance with the opposite sex. This highlights the gap between the reality of sexuality, the competing ideologies on the nature of sexuality, and how sexuality is treated in practice.

Critics of ftm-inclusive porn highlights the tensions between homosexuals who insist that sexuality is based on biological sex and queerness where sexuality can hinge on subjective gender experience. The first group claims to base its legitimacy on biological sex. Stating that gender identity does not exist and that all that matters is biological sex. The second group posits that gender is also based on subjectivity. Therefore, a gay man having sex with a ftm trans man is gay sex due to the participants' subjective nature.

Within LGBTQ+ and LGB spaces, displays of identity orthodoxy—calling out or shaming perceived deviants—function as a form of moral performance that Calvinist lucidity would regard as a psychodramatic act, mistaking emotional intensity for moral or social standing.

By tempering queer discourse’s theatrical impulses with Calvinist lucidity, we can cultivate an ethic that values diagnostic honesty, self‑mastery, and unmerited clarity—qualities needed both online and off to navigate the turbulent waters of identity in the twenty‑first century.

The debate over what defines sexuality—whether biological sex, gender identity, or the endless performance of both—reveals more than a question of labels. It exposes the fragility of collective identities and the performative burdens placed on individuals. Calvinist lucidity offers a surprising remedy: not by prescribing fixed categories or idealizing liberation, but by demanding that desire and identity stand coram Deo, under the unflinching light of divine scrutiny. In doing so, it transcends the binaries of affirmation and rejection, offering a third way: a posture of sober self‑examination and courageous authenticity.

In this ethic, queerness is neither erased nor sanctified, but approached as a site of dangerous knowledge, where truth can wound and clarify in equal measure. Here, the individual does not seek spectacle or solidarity alone but wrestles with their own heart, choosing with clarity what to affirm and what to relinquish. Ultimately, the question of “What is queer identity?” becomes not a matter of social verdict but a lifelong inquiry carried before the face of God. Only in that relentless clarity can one navigate both the promise and peril of desire.